When artist and filmmaker John Severson launched an early version of Surfer magazine in southern California in 1960, the U.S. surfing population—confined at the time almost entirely to Hawaii and southern California—was so small that he wasn’t sure there were enough surfers and advertisers to support the publication. Severson, who once cited Gauguin, Picasso and Abstract Expressionism as his principal influences, originally designed the 36-page magazine as a collection of prints of his own surf photography, pen-and-ink drawings, cartoons and illustrations, and short fiction to promote live screenings of his surf movies.

Despite his qualms, Severson (1933-2017) forged ahead with Surfer, eventually benefitting from the nascent boom in popularity of surfing among California teenagers that would explode across America to the East Coast by the mid-‘60s and then spread to the rest of the world. He later expanded Surfer to 12 issues annually and its circulation would top more than 100,000 by the end of the decade.

Despite his qualms, Severson (1933-2017) forged ahead with Surfer, eventually benefitting from the nascent boom in popularity of surfing among California teenagers that would explode across America to the East Coast by the mid-‘60s and then spread to the rest of the world. He later expanded Surfer to 12 issues annually and its circulation would top more than 100,000 by the end of the decade.

Severson’s academic training—he held a master’s degree in art education–and natural gifts as an artist, editor and writer combined to create what would become the definitive voice of the surfing world and its culture. When he started Surfer 65 years ago, the surfing market was virtually nil; today the global surfing industry is estimated to be worth more than $12 billion.

The chronicles of surfing abound with soulful innovators like Severson, whose story underscores the deep historical connections that bond surfing and artists. Their creative spirit persists today through the contemporary surfer/artists who continue to shape the narrative—turning surf culture into a vital platform for personal expression.

“Summer Salt: Fresh perspectives in print, paint, photography, sculpture, and scrimshaw,” the current exhibition at the Zach Gallery in Easton, explores these intersections in a modern context, showcasing the work of five East Coast surfer/artists: Peter Spacek, Scott Bluedorn, Scott Szegeski, Ben McBrien and Nick LaVecchia.

“All five of the artists included in this exhibition are surfers,” said Aynsley Schopfer, manager of the Zach Gallery. “I perceive their art as a response—a dialogue with humanity–from their experience in the water. Their choice of materials and subject matter reflects their relationship and reverence for not only the ocean, but the natural world at large, which feels particularly pertinent to a community on the edge of the Chesapeake Bay. In my observation, few people understand and respect nature more than surfers.”

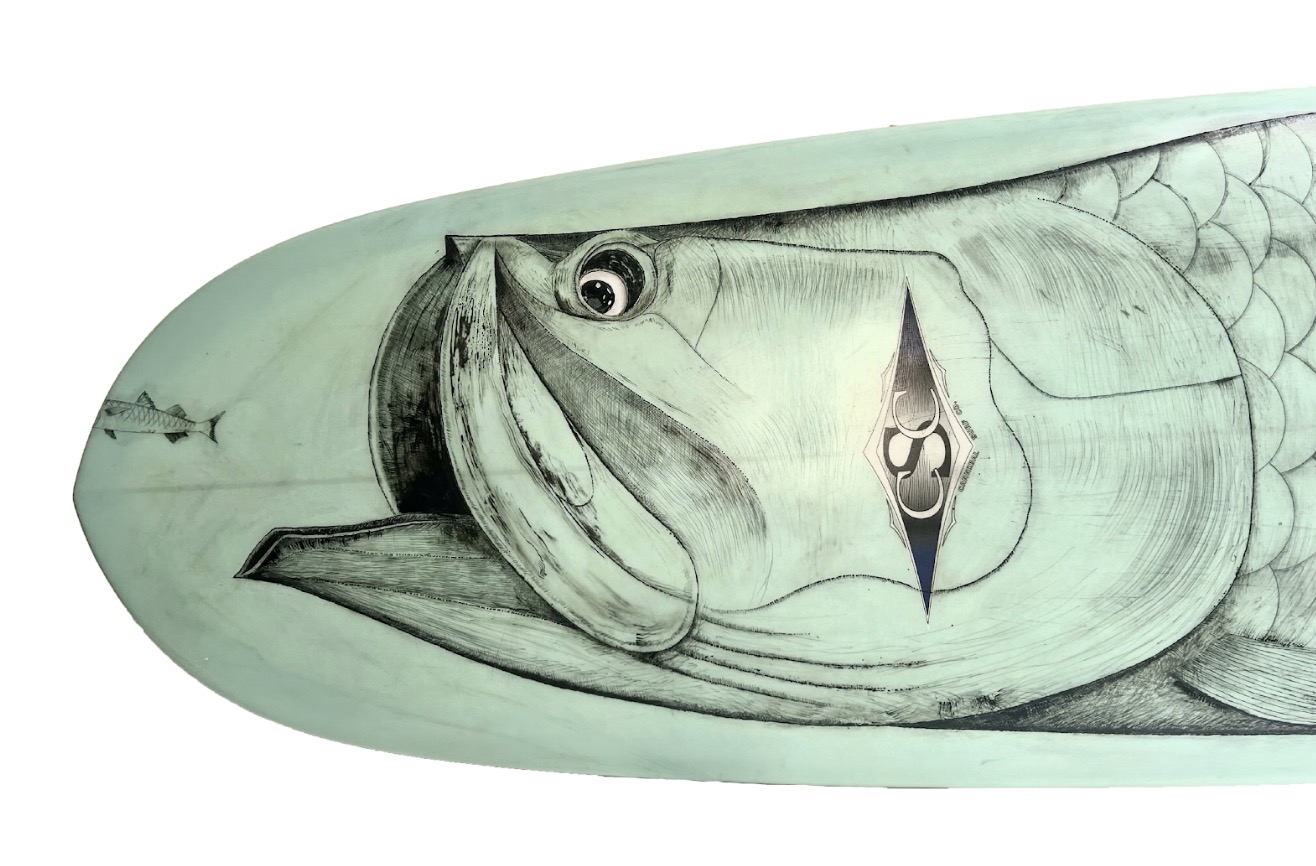

Spacek, a Santa Barbara transplant who lives and works in Long Island’s East End, specializes in “modern scrimshaw,” a technique inspired by the ancient maritime craft of etching images onto whale bone and walrus tusks. Using discarded polyurethane-foam-and-fiberglass surfboards and fragments as his canvas, he thoughtfully repurposes materials that would otherwise be scrapped. Their luminosity and weathered texture, acquired through years of exposure to the elements, lend them a unique character. The show includes one of his earliest examples of this technique, Indo Point, etched on a surfboard he shaped in 1973.

As a surfer Spacek features prominently in William Finnegan’s dazzling memoir Barbarian Days: a Surfing Life, winner of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for biography/autobiography. Finnegan grew up surfing in California and Hawaii and later moved to New York City as his journalism career flourished. As a staff writer at the New Yorker magazine, he and his wife, Caroline, a lawyer, had settled into a comfortable middle-age professional life in Manhattan when he happened to meet Spacek in Montauk, a surf town at the far eastern end of Long Island. Spacek’s nervous enthusiasm for surfing was boundless. His “stoke” quickly infected Finnegan and the two surfers embarked on a series of trips over nine years to Madeira, a Portuguese archipelago situated in the north Atlantic, 300 miles from the Moroccan coast. Madeira’s waves undulate unimpeded out of deep water, like those in Hawaii, striking the island with staggering size and power. Finnegan’s chapter on Spacek is a harrowing account of gargantuan waves, horrifying wipeouts and hold-downs, near drownings, serious injuries and blood left on the rocks. For Spacek and Finnegan, it was euphoria.

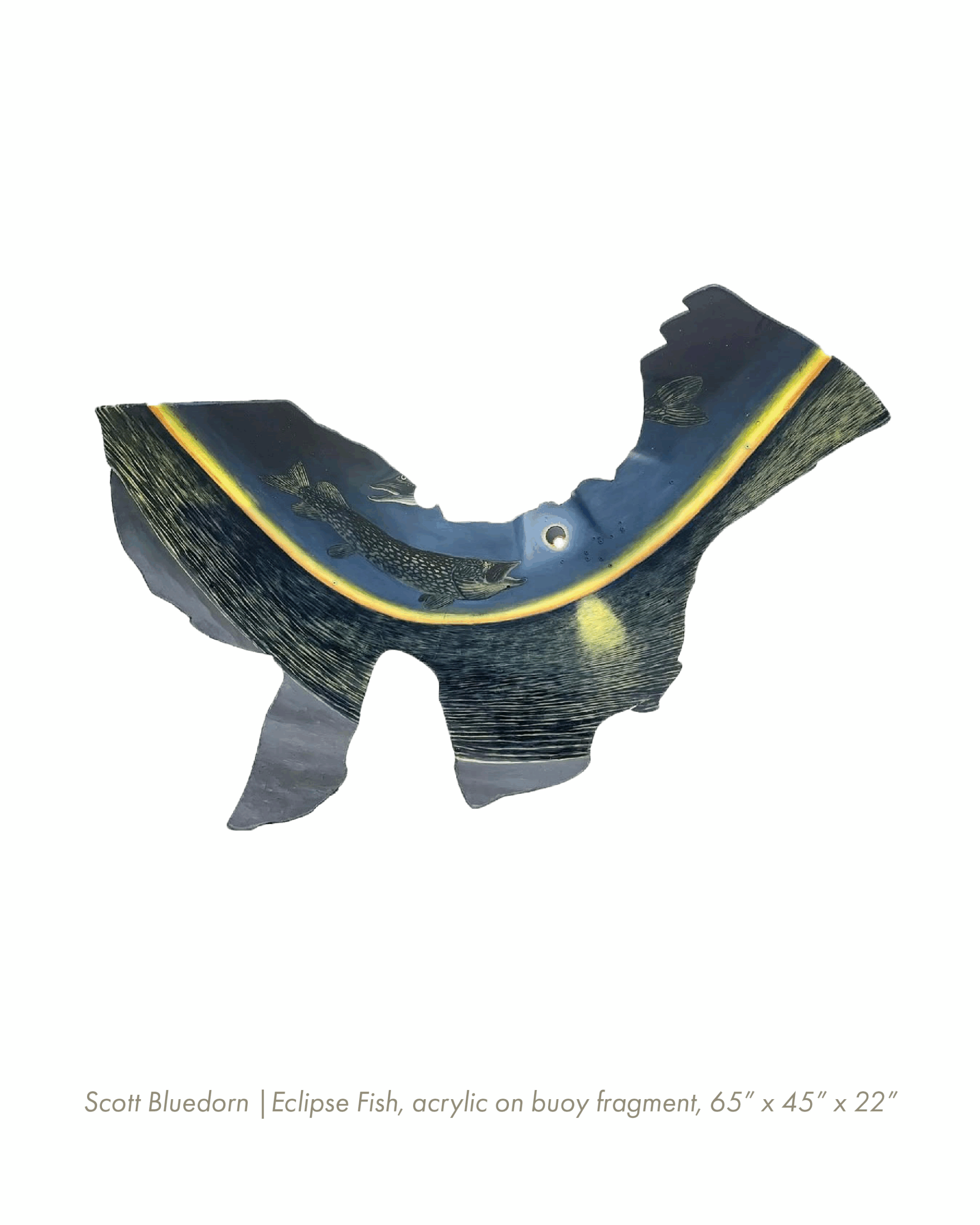

Scott Bluedorn, another Long Island-based surfer/artist, works across an impressive array of media, including painting, drawing, printmaking, collage, installation and found-object assemblage. Bluedorn, who earned a bachelor’s degree at the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2009, produces surreal imagery inspired by maritime history, cultural anthropology, myth, supernatural themes and the natural world to distill a vision he deems “maritime cosmology.” One of his larger pieces on view at the gallery, Eclipse Fish, is an acrylic painting on a found object: remnants of a plastic industrial buoy that washed ashore in a storm.

“The painting is based on my experience of the total solar eclipse witnessed on Lake Ontario and the disoriented salmon and pike I saw swimming around after the event,” Bluedorn says.

Scott Szegeski, a New Jersey-based artist and avid surfer, revisits an ancient technique in Japanese printmaking called gyotaku to impress full-size images of surfboards on paper. The ink-based practice was originally used by Japanese fishermen in the 19th century to document and archive their fish catches. The technique lets Szegeski preserve all of the unique dings, gashes, scratches and other wear-and-tear marks that a surfboard accumulates after a life in the ocean.

After years of printing his own surfboards, Szegeski began receiving requests for his gyotaku prints from local surfers who wanted to carve out a memory in time of their favorite board. A prime example of the gyotaku technique in the show is Big Fish, a print of a board shaped in California for East Coast legend Scott Duerr, a member of the New Jersey and the East Coast surfing halls of fame.

Big Fish also displays the work of “wood wizard” Ben McBrien, founder of Farmhaus, who built the walnut frame for the piece. McBrien says he established Farmhaus, his one-man furniture studio, as a young father with a need for a flexible schedule and “to fund his surfing addiction.” His work focuses on finding function, purpose and beauty in the discarded materials from Philadelphia’s outdated housing. Also in the show are several Farmhaus sculptures, meticulously carved wood pieces treated with shou sugi ban, a Japanese technique of charring wood. Sounder, a whale’s tail carved from two poplar-wood sections and attached with a brass hinge, is exceptional in its simplicity and beauty. McBrien recently moved Farmhaus from Philadelphia to Asbury Park to be closer to the surf.

Farmhaus also collaborated with renowned Maine photographer/surfer Nick LaVecchia on another piece at Zach, constructing an oxidized-ash frame for LaVecchia’s wistful Portal No. 44, a Chromaluxe aluminum print of a misty moon (or sun) hovering above a dreamy sea. LaVecchia’s work reflects his love and respect for the forces of nature that shape the rugged Maine coast, where he lives in a modern, sustainable homestead on the family farm. He brings an eye for humanity’s place in the world and the images he creates represent the purity and natural beauty of every subject. His work has been highly sought after by major international corporations, including Apple, Bose, BMW, Google, the North Face, Toyota and Yeti.

Perhaps more notably, LaVecchia is just as celebrated as a photographer in the surfing world. An article on LaVecchia and his work in a 2021 issue of The Surfer’s Journal, a ravishingly elegant bimonthly, is accompanied by a wide-ranging selection of photos that capture the picturesque rawness and pristine blue-green waves that make coastal Maine so potently alluring for surfers. Lavecchia’s photos made surfers from all over the world want to be a part of Maine surfing, according to the story.

While art and surfing are serious business for these artists, they also know that both pursuits can also be fun and joyous.

“For a summer exhibition it was important to evoke a fresh, jovial mood, where you can almost breathe the salt air with an unpretentious elegance,” Schopfer said.

Richard W. Walker is a former staff writer at ARTnews magazine in New York and a longtime surfer.

Summer Salt: fresh perspectives in print, paint, photography, sculpture, and scrimshaw is on view at the Zach Gallery through September 6 at 17 South Washington Street, Easton. Gallery hours are Wednesday-Saturday10-4 and by appointment.

Write a Letter to the Editor on this Article

We encourage readers to offer their point of view on this article by submitting the following form. Editing is sometimes necessary and is done at the discretion of the editorial staff.