The collection of the National Gallery of Art (NGA) includes art made by the best painters of the High Renaissance. The Medici of Florence, along with other wealthy families, studied classical art and literature. The visits of the Byzantine Emperor John Palaeologus to Florence in 1423 and 1439 served as a catalyst. Needing funds, Palaeologus sold many Greek and Roman art works to the Medici. Cosimo de Medici (1389-1454) began the collection. Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492) was an insatiable collector.

“Lorenzo de Medici” (c.1513-20)

Attributed to Andrea del Verrocchio, or his workshop, the painted terracotta image of “Lorenzo de Medici” (c.1513-20) was fashioned after his death mask. The subject wears the simple padded and draped headdress of a Florentine citizen, not the elaborate crown that would represent his status. In a document dated 1471, Lorenzo recorded his calculation of the Medici expenditure of 663,000 florins ($460 million) for works of art and for charity. He wrote, “I do not regret this for though many would consider it better to have a part of that sum in their purse, I consider it to have been a great honor to our state, and I think the money was well-expended and I am well-pleased.”

“Guiliano de Medici” (1475-78)

The terracotta portrait (1475-78) (24”x26”x11”) of Lorenzo’s younger brother Guiliano de Medici is by Andrea del Verrocchio (c.1435-1488). He was a sculptor, painter, and goldsmith, the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci, and a Medici favorite. The portrait was commissioned for Giuliano’s coming of age celebration when a joust took place in his honor. Guiliano was the handsome, athletic, and popular brother and was depicted in several works of art. His Roman style armor is decorated with a winged face. The bust may have been originally painted and worn a metal helmet. Guiliano and Lorenzo were co-rulers of Florence. Guiliano was assassinated in the Pazzi conspiracy to take over Florence on Sunday, April 28, 1478.

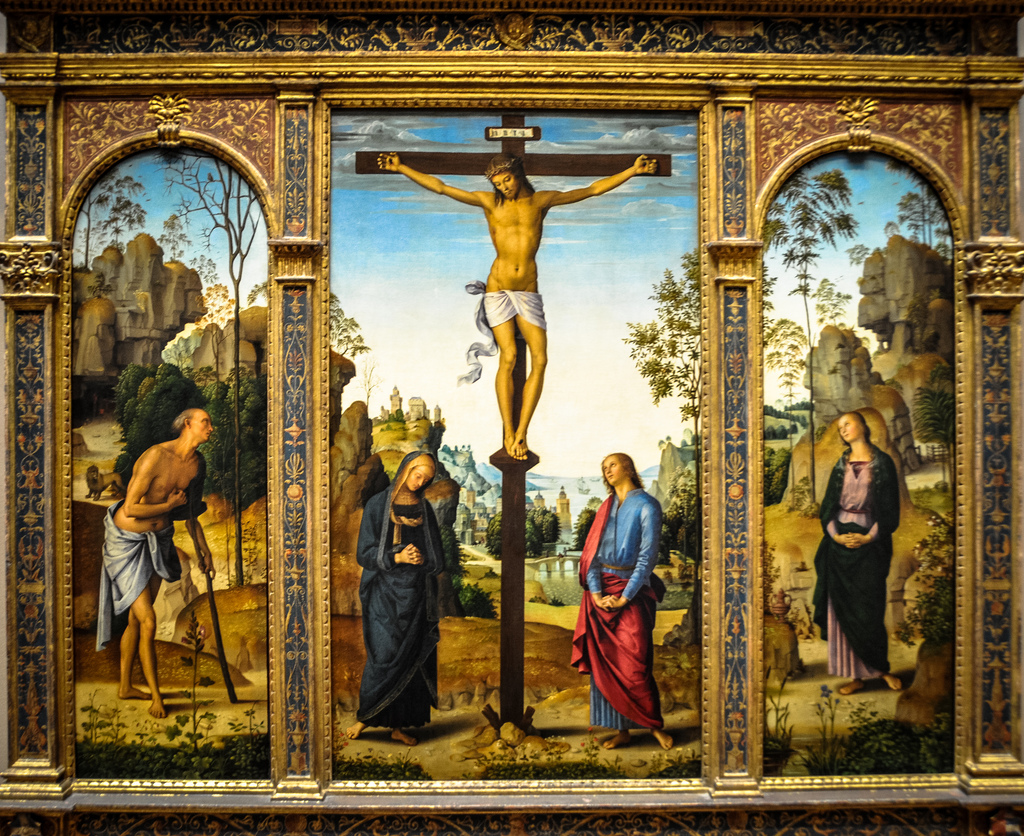

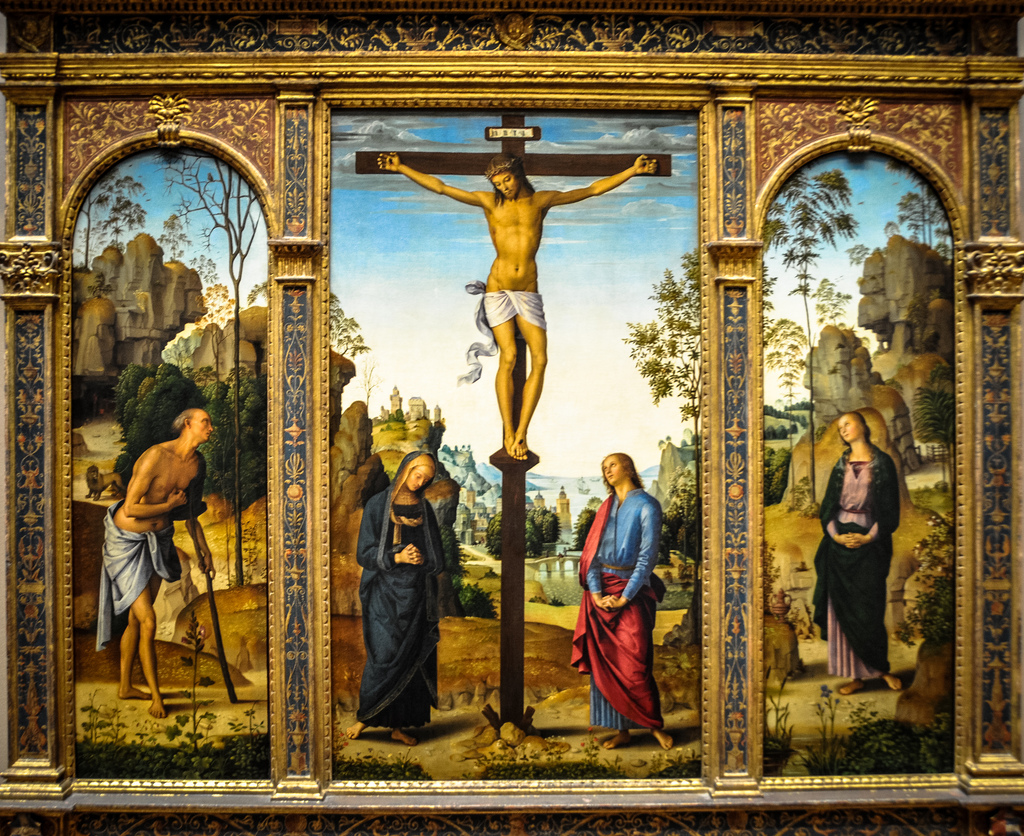

“Crucifixion with the Virgin, St John, St Jerome and St Mary Magdelen” (1482-85)

“Crucifixion with the Virgin, St John, St Jerome and St Mary Magdelen” (1482-85) (53”x65”) (oil) was a commission to Pietro Perugino (c.1446/52-1523) for the chapel of the Dominican monastery church of San Gimignano. Little is known about Perugino’s early life. He was trained in the workshop of Verrocchio in Florence with da Vinci, Ghirlandaio, Filippo Lippi, and others. Piero della Francesco taught him perspective. A celebrated painter in Florence, Perugino was called upon by Pope Sixtus IV in 1481 to paint the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Perugino was Raphael’s teacher.

“Crucifixion with the Virgin, St John, St Jerome and St Mary Magdelen” was painted while he was working on the Sistine. Perugino was one of the first Italian painters to use oil paint that gives the work vibrant colors. His expertise in perspective is clearly illustrated with the vast landscape of mountains in the center panel, revealing streams, bridges, towns, castles, and the distant ocean and boats. Typical of Renaissance paintings, sunlight fills the scene. The well-realized figures quietly meditate on the crucified Christ. Their pointed toes are a unique aspect of Perugino’s work.

Influenced by Flemish painters, who introduced painting with oil-based paint, Perugino included a narrow floral carpet containing a variety of flowers and herbs at the front of the canvas. All are symbols of the Virgin. Perugino painted a skull at the base of the cross. Golgotha (place of the skull) (Calvaria in Latin) was used for executions, noted in Matthew 27:33: “They came to a place called Golgotha.”

St Jerome, at the left, always was depicted as an old man who lived in a cave in the desert. Coming down the path is the lion that he helped by removing a thorn from its paw. The lion then became Jerome’s protector. Opposite is Mary Magdalen who, after the death of Christ, retreated from the world to live in the wilderness. She typically is portrayed with very long hair.

“Madonna and Child” (1500)

Perugino’s “Madonna and Child” (1500) (oil) (28”x20’’) was the model for the 1986 United States religious postage stamp.

“Alba Madonna” (1510)

“Alba Madonna” (1510) (tondo 37’’) (oil) was painted by Raphael Sanzio (1483-1520) of Urbino, Italy. Of the three famous masters of the High Renaissance, Raphael was the youngest. Perugino was his teacher in Umbria from 1480 to 1500. He arrived in Florence in 1504 with a letter of recommendation: “The bearer of this will be found to be Raphael, painter of Urbino, who, being greatly gifted in his profession, has determined to spend some time in Florence to study. And because his father was most worthy and I was very attached to him, and the son is a sensible and well-mannered young man, on both accounts, I bare him great love.’’ Raphael was 21 years old, Michelangelo was 30, and da Vinci was 42. All were actively working in Florence. Raphael, an astute observer and eager to improve his craft, learned the best lessons these older artists’ work had to offer. He became a favorite of wealthy collectors.

The “Alba Madonna” is an excellent illustration of what Rapheal absorbed and what he brought to the easel. The painting was commissioned while he was in Rome, painting the Papal apartments in the Vatican for Julius II. Prelate Paolo Giovio, physician and writer, most likely commissioned the work for the altar in his church in Nocera. The Madonna, Christ, and John the Baptist became a popular grouping of subjects, although no Biblical passage refers to the three having met.

Raphael, a master of composition, used the triangle to position and pose the figures, the approach made popular by da Vinci. Mary’s pose forms a triangle–her head at the top, her shoulders angled downward, her arms forming the sides, and her seated position on the ground the base. Her bent knee forms another triangle. Mary looks toward her son, who looks at John, who looks back, completing the triangle. Smaller triangles are formed by the positions of Christ’s knee and John’s elbow. The neckline of Mary’s pink gown forms a triangle, pointing downward, and is matched by the pink triangle on the ground. The repeated use of triangles helps to stabilize the composition within the circle.

The composition is further stabilized by the perfectly positioned horizontal line in the landscape. The peaceful, sun filled landscape echoes the gentle curves, angles, and colors of the work. Circles are also used to repeat the round shape of the frame. Mary’s face, hair, and blue headdress, the blue gown resting on her shoulders, the roundness of Christ’s and John’s bodies, the stump on which Mary rests her arm, and the flow of her gown on the ground support the circle. The musculature of the children’s figures provides evidence of Raphael’s attention to the work of Michelangelo on the Sistine ceiling. Christ holds a small cross. Mary holds the Book of Knowledge. The line of her arm and leg form the hypotonus of a triangle. The three quietly contemplate the future.

“Ginevra de Benci” (1474-78)

“Ginevra de Benci” (1474-78) (oil) (15”x14”) is the only known painting in the United States by da Vinci. The National Gallery announced in February 1967 the purchase of the painting for a record setting $5 million. It was viewed by almost 1,000 people in the first hour it was on display on March 17 of that year. Members of the Medici circle wrote ten poems about Ginevra’s beauty, and Lorenzo wrote at least two sonnets to her. She was educated, a poet, and said to be a good conversationalist. She was sixteen when her portrait was painted, most likely for her engagement. The lower section of the painting has been cut off.

Traditional Florentine portraits presented a profile view of the sitter. Leonardo was one of the first to paint a three-quarter view. Ginevra looks out at the viewer, but she does not make eye contact. As in the profile paintings of the time, people of importance did not engage with viewers. In his early twenties at the time, Leonardo would not paint the “Mona Lisa” until thirty years later. “Ginevra” was one of his first oil paintings. He used the flexibility of the medium to depict soft shadows to mold Ginevra’s face.

The juniper behind her head takes up most of the composition. It was a symbol of female virtue, and in ancient Greece the tree was sacred to the Goddess Artemis. It was thought to be protective because of its spikey needles and was burned to cleanse temples and homes. The needles provide a contrast to Ginevra’s soft, golden curls. The blue sky viewed through the tree branches matches the blue laces of her gown. The zig zag laces draw the viewer’s eye toward the distant landscape.

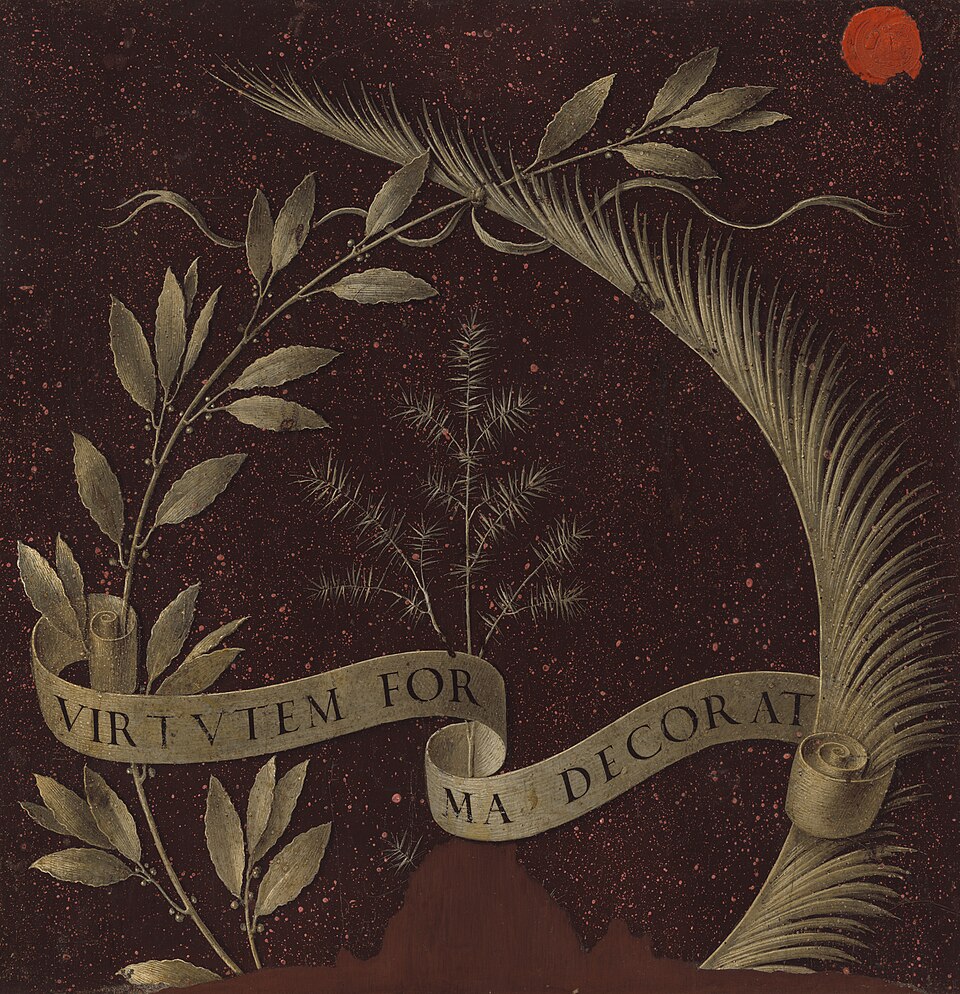

“Ginevra de Benci” (verso)

The verso, or back side of the canvas, adds another level of symbolism. A sprig of juniper is painted in the center of a wreath made of laurel and palm branches. Apollo wore laurel branches as a victory wreath. Palm branches can represent fertility, purity, and beauty. They also are associated with Christ’s entry into Jerusalem. Encircling the three branches is a scroll with the Latin inscription that translates to Beauty Adorns Virtue.

Beverly Hall Smith was a professor of art history for 40 years. Since retiring to Chestertown with her husband Kurt in 2014, she has taught art history classes at WC-ALL and the Institute of Adult Learning, Centreville. An artist, she sometimes exhibits work at River Arts. She also paints sets for the Garfield Theater in Chestertown.