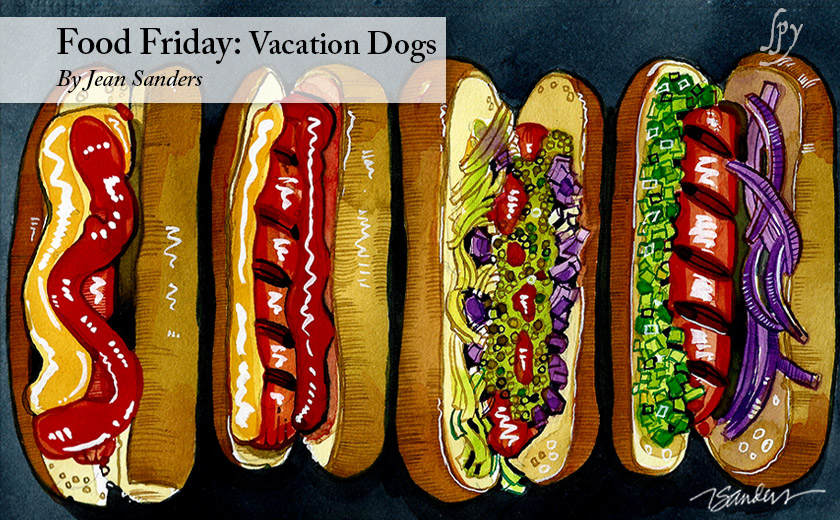

Mr. Sanders, Luke the wonder dog and I are off for a little holiday respite in the mountains of North Carolina for the Fourth of July holidays this week. We are planning to grill some hot dogs in honor of our national holiday. Enjoy a column from a couple of years ago, when we had moseyed up to New England for a change of scene!

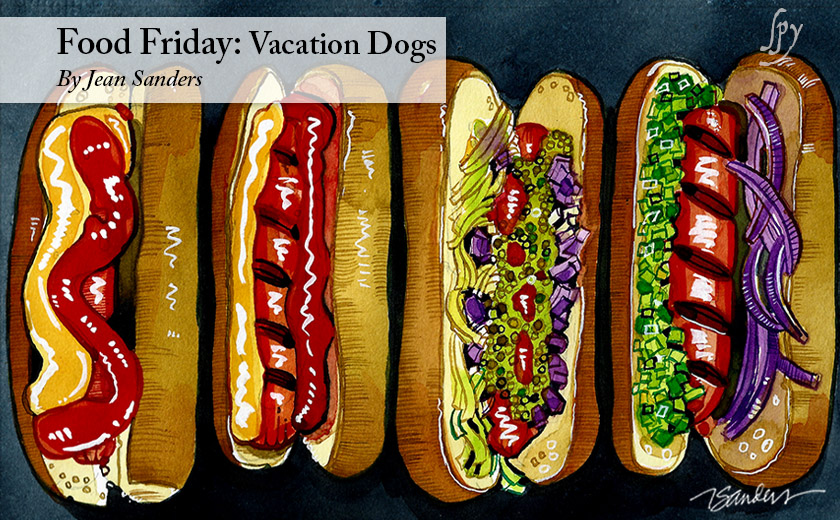

Sometimes I forget that we live in a country that is so vast and diverse that a New England hot dog is wildly different from a Chicago-style hot dog, and neither of them is like a hot dog from Texas, or from California. And this is one of the great American qualities – we are true blue and we love our regional delicacies.

In Boston, a Fenway Frank is boiled first, and then lightly grilled. (It is served in a split-top roll, which is also used for the best sort of lobster rolls: Split-top Roll) The Puritans among us prefer garnishing a Fenway Frank with just a thick wiggly trail of spicy mustard. But since this is America, feel free to pile on your own favorites.

As you travel west to Chicago, you will observe that the Chicago-style hot dog is a completely different creation. Chicago-style hot dogs are cooked in butter in a pan, and then served in warm, poppy-seed rolls, with lots of veggies on top. Chicago-style dogs are “dragged through the garden”: topped with sweet pickle relish, chopped onions, pickled peppers, tomato slices and sprinkled with celery salt. Have you been watching The Bear? You’ll know then how popular these franks are.

Then you’ll mosey down to Texas, to encounter the Hot Texas Wiener , a frank cooked in hot vegetable oil. If you place an order for a “One”, you’ll get a blisteringly hot frank topped with spicy brown mustard, chopped onions, and chili sauce. Yumsters.

As you continue west, and stop in Los Angeles for a some street food, you will encounter an L.A. Danger Dog. This frank is wrapped in bacon! I cannot imagine the state that Gwyneth and Meghan call home would do anything so decadent and audacious as a grilled, bacon-wrapped hot dog. More controversial to a hot dog purist are the toppings: catsup, mustard, mayonnaise, sautéed onions, with peppers, and a poblano chile pepper. Catsup? Mayo? But to be polite, you must eat like a local, and it will be deelish.

Common sense teaches us to not use catsup on our franks after the age of 18. You might as well make bologna sandwiches with Wonder bread, and douse them in catsup.

Have you ever seen the Oscar Meyer Weinermobile on the road? I can remember driving on a Florida highway once, and suddenly, puttering alongside us, was the Weinermobile. What a cheap thrill that was! Sadly, now it is called the Frankmobile. Time marches on.

You can follow the Frankmobile on Instagram:

July is National Hot Dog Month, and the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council says that some of the top hot dog consuming cities include: Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Phoenix, Atlanta, Detroit, Washington, DC, and Tampa. You’ll want to brush up on your hot dog etiquette https://www.kplctv.com/2019/07/03/hot-dog-etiquette-dos-donts-during-fourth-july-holiday/, I’m sure.

And here are the official rules for Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, in case you want to try this at home.

NPR 1A – Hot Dogs

“A hotdog at the ballgame beats roast beef at the Ritz.”

— Humphrey Bogart

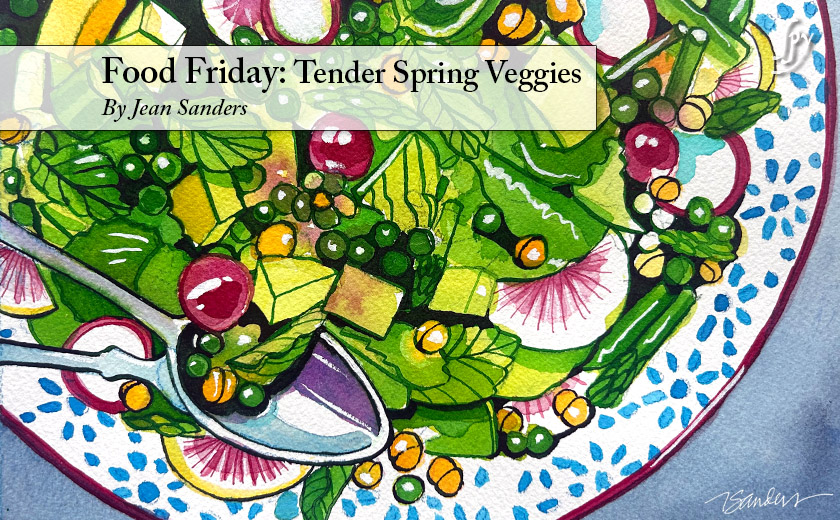

Jean Dixon Sanders has been a painter and graphic designer for the past thirty years. A graduate of Washington College, where she majored in fine art, Jean started her work in design with the Literary House lecture program. The illustrations she contributes to the Spies are done with watercolor, colored pencil, and ink.