I love numbers. I love everything about them. I love how they give me information. I love how they categorize things. I love how they provide a window into understanding.

I love to analyze numbers. I love to use numbers to find trends, to discover relationships, to predict behavior, to explain the world.

Here are some key statistics today. There is a 26.2% decline in U.S. drug overdose deaths. The GDP has an average annualized growth rate of 4.4%. Global population has reached 8.1 billion. U.S. median household income was approximately $82,000. From these numbers we can explain and see the world.

Yet I also know how dangerous numbers can be. Numbers allow us to remove humanity and replace it with hypotheses, things. Numbers can reduce us to points on a chart. A single number can define us. A group of numbers, demographics, can categorize us.

Numbers are really just a language that we use to classify, categorize, understand, that’s it. Yet we give so much weight to numbers.

Look at IQ. Since I am classically trained in test development, I understand exactly what IQ is. When we construct tests, we have to compare them to something to see if they are right (called construct validity). So how did we really decide intelligence? Well, over a hundred years ago, a bunch of white men decided what intelligence was and then developed questions to measure their view of intelligence. While IQ tests have been modified and changed since then, when you strip it of everything, IQ is just a number that is based on self-declared intelligent people’s view of intelligence. See how meaningless it really is? Fortunately, now there are multiple types of intelligence.

Numbers can be very dangerous.

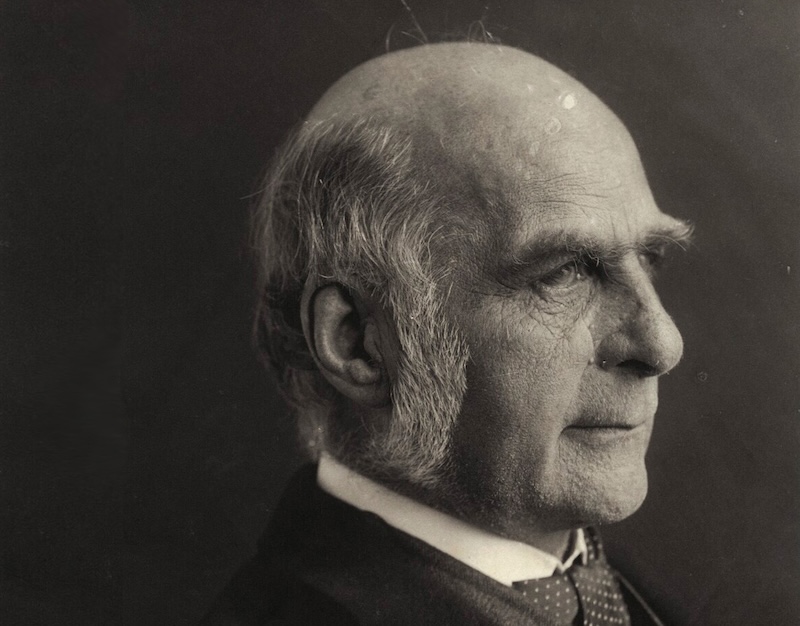

This is a story about one of my heroes, arguably one of the smartest men who ever lived. His name was Sir Francis Galton. He was a genius by any standard. He developed statistical tests to measure relationship (correlation). He discovered the phenomenon of regression toward the mean. He created fingerprint forensics. He devised the first weather map. He was the first to establish a complete record of short-term climatic phenomena on a European scale. He invented questionnaires and a whistle to test hearing ability. But mostly he loved collecting and analyzing numbers.

Inspired by his cousin Charles Darwin’s Origin of the Species, he decided to use his understanding of numbers to aid evolution. He created and coined the term Eugenics. With Eugenics, he was able to reduce humanity to a number, based on his view of intelligence, he believed that he could predict intelligence by race.

It had disastrous consequences.

In the early 1900s, scientists took this data and ran with it. Eventually moving to body metrics, head size; basically everything that they could measure about people at the time. They used this data to predict who would be successful, who would be a criminal, who should be sterilized, who should be killed.

Galton’s work was used by the Nazis, it was used to sterilize thousands of people, it was used categorize intelligence based on race, gender, and head size.

So, numbers are fun, they are enlightening, they allow us to prioritize, they help us understand. They give us a view of where we are headed.

But we can never allow ourselves to forget who is hiding behind our numbers.