Maryland has long been touted as “America in Miniature,” and while that venerable tourism-boosting label refers to geographical diversity, the Maryland-as-microcosm description perfectly encapsulates the Old Line State during the Civil War. Perched on the faultline of a nation ripped in two, Maryland was home to North America’s largest free Black population, but it also was home to a vociferous secessionist element and had a slaveholding governor (pro-Union but pro-slavery Thomas Holliday Hicks of Dorchester County) at the war’s outset.

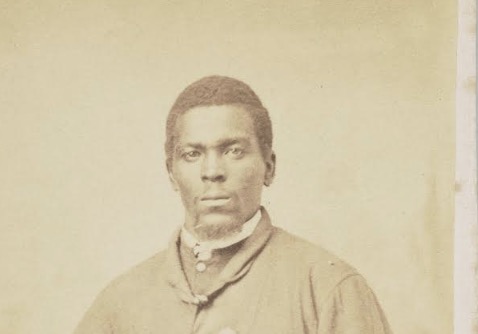

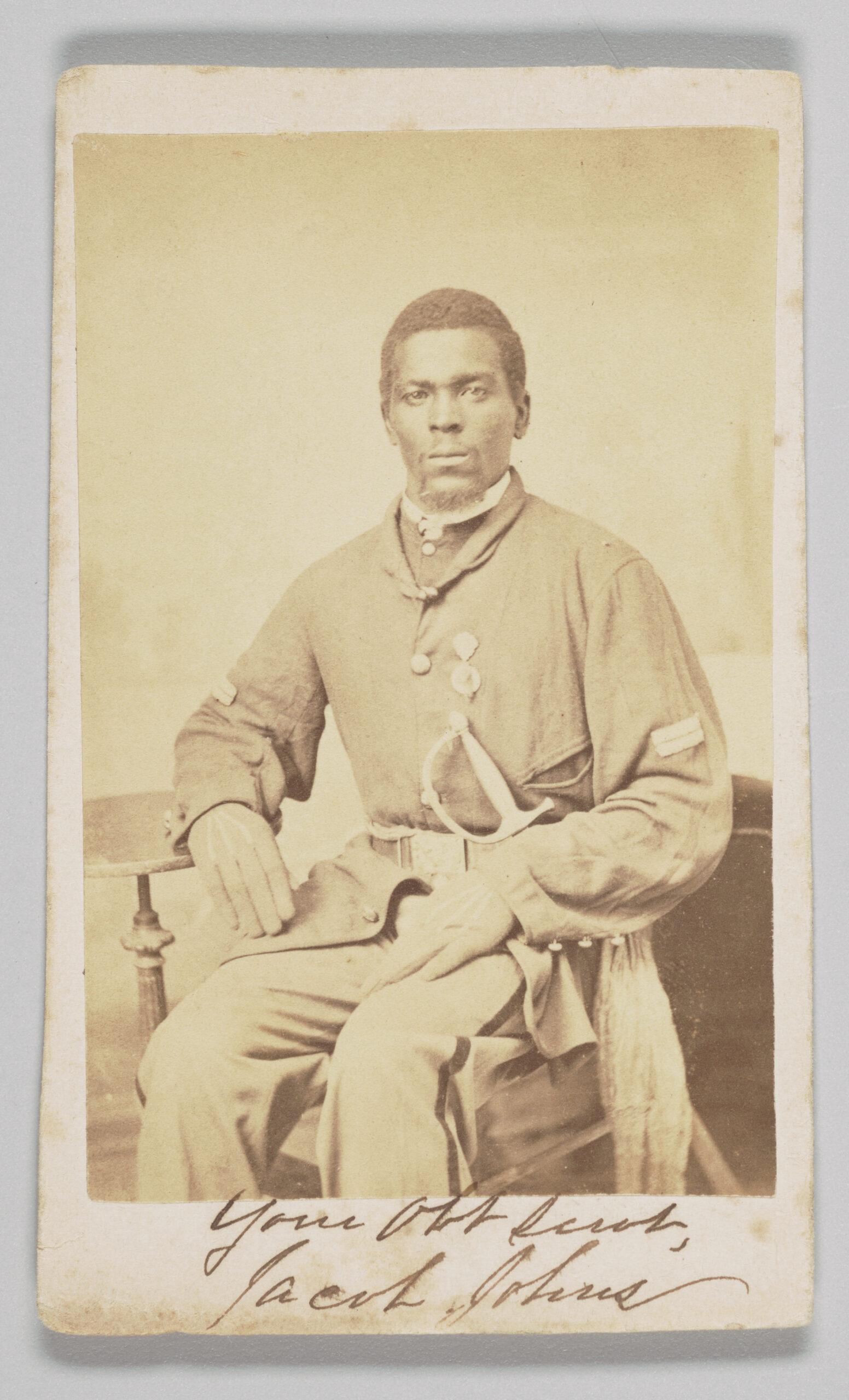

Jacob Johns of the 19th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, Company B—a rare photograph of one of Talbot County’s African American Civil War soldiers in uniform. COURTESY TALBOT HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Maryland’s schizophrenic duality manifested on the local level as well. In Easton, rival pro-Union and pro-secessionist newspapers put their opposing spins on every development from the front. Cousins from Trappe fought against each other at Culp’s Hill during the Battle of Gettysburg. Few, if any, other chapters in Talbot County’s history are as rich with such fascinating complexities.

And now, a new exhibit at the Talbot Historical Society is shedding light on a compelling aspect of that story—the role of Black troops in the war. “With Valor and Honor: Talbot County’s United States Colored Troops (USCT) During the Civil War” recently opened at the Society’s museum at 25 South Washington Street in Easton and will be on view through next April.

The product of six months’ worth of exhaustive research by Historical Society staffers and volunteers, the exhibit has begun to enjoy a turnout that’s “been incredible,” said Operations Manager Kayla Weber. “A lot of people from Talbot County are coming out, which is great to see. I think word-of-mouth is definitely helping it.”

Through exhibit panels, video clips, maps, touch-screens, artifacts, family memorabilia, and historical documents, “With Valor and Honor” captures the inspiring story of how African American troops from Talbot joined the cause in impressive numbers and donned the Union blue during the latter phase of the war.

By 1863, a profound war weariness was settling in for both North and South. Food riots broke out in the Confederate capital of Richmond, and an unpopular draft that exempted wealthy plantationers based on how much human chattel they owned (the “Twenty Negro Law”) was leading to outcries that the whole bloody tragedy was “a Rich Man’s War and a Poor Man’s Fight.” In the North, the New York City Draft Riots in the summer of 1863 raged for days in a roiling outburst of class and racial tensions. For both the Union and the Confederacy, as the war dragged on and enthusiasm faded, voluntary enlistments had fallen sharply, and conscription was merely adding to the general discontent.

But President Abraham Lincoln had a powerful resource to tap into that the Confederacy lacked—a resource for whom this war had more profound significance and relevance than it possibly could have for any other group of potential enlistees. And so was born War Department General Order 143, establishing the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in May 1863.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton appointed Colonel William Birney, son of the abolitionist James G. Birney, as Maryland’s mustering officer for the USCT. Ostensibly, Birney was to recruit only from Maryland’s sizable free Black population; since Maryland was in the Union, it was exempt from the Confederacy-targeting, slavery-eradicating dictates of the Emancipation Proclamation, putting the state’s enslaved populace in an ironic and paradoxical limbo.

But in the practical realities of the moment, the abolitionist’s son found it was better to be blissfully indiscriminate in his recruitment efforts, whether the enlistee was free or enslaved. Throughout the summer and fall of 1863, Birney’s recruitment steamboats, often replete with a rousing Black marching band and smartly turned-out Black troops, plied the rivers of the Eastern Shore, and hundreds of enslaved men left the plantations to fight. Two hundred left Easton that September on the steamer Champion, and more soon followed on the steamer Cecil. Elsewhere on the Shore, the Chestertown News reported that, when a steamer hove to in Kent County that September, it appeared that “the negroes had previous notice of the coming of the boat and flocked to the shores in such crowds that many had to be left behind. The number carried off is estimated at from 150 to 200, including nearly every able-bodied slave in Eastern Neck.”

Down on the Lower Shore, hundreds more were flocking to the steamers John Tracy and Meigs, while the Balloon and Cecil culled some 130 additional recruits from the Chesapeake oyster fleet working from the mouth of the Patuxent to Tangier Sound. Among Maryland’s slaveholders who were loyal to the Union, indignation was rising.

Then, that October, with the War Department’s issuing of General Order 329, the regulations for USCT recruitment were more specifically delineated: Men bound in slavery could enlist if the slaveholder consented—and by so doing, he would get up to $300 as manumission compensation. Further, if a county’s recruitment quota was not filled within 30 days, the Bureau of Colored Troops had the power to recruit from the enslaved population without the slaveholder’s consent. (Even then, the slaveholder would be compensated—if he avowed his loyalty to the Union.)

By late October of 1863, there were Bureau of Colored Troops recruitment stations from Havre de Grace to Princess Anne, at Oxford, Queenstown, Chestertown, and other locations throughout the state. Ultimately, more than 8,700 Maryland Blacks rallied to the flag.

And more than 600 of those troops hailed from Talbot. They ranged in age from 16 to 46. About 56 percent of them had left slavery behind to enlist, while about 44 percent of them were free men already when they put their lives on the line to fight for the Union.

Forty-eight of them would be killed in battle. One hundred of them died from disease. Seven of the 17 who ended up as prisoners of war died in captivity in hellish prison camps. Fifty-four were wounded but survived and were discharged. A fortunate 180 of them completed full terms of enlistment. And there were 168 of them whose fates remain unknown.

As the “With Honor and Valor” exhibit elucidates, their numbers were spread out across five infantry regiments. Some saw action during General Ulysses S. Grant’s May 1864 Bermuda Hundred Campaign, or at the horrific July 1864 Battle of the Crater (described by Grant as “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war”), or at the September 1864 Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. (Talbot Countian Gilbert Adams of the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment, Company D, was captured at Chaffin’s Farm. After enduring seven months as a prisoner of war, he escaped and reported back for duty.)

After the war, they came home to a different world, one where slavery no longer existed alongside freedom, and they founded new Talbot County communities such as Unionville, Copperville, and Eastfield. “With Valor and Honor” does a consummate job of chronicling this postwar phase of the story, and such legendary local-historical figures as Nathaniel “Nace” Hopkins, John Copper, and the Unionville 18 are now presented together in the broader historical context, many of the displays augmented by relics preserved by the families of these men. In viewing all this, one feels a growing awareness of continuity, of the past as prologue, of individual family histories and a region’s larger history all bound together as a collective whole.

“Being able to provide this information to the community” has been rewarding, observed Weber, “because we have so many descendants of these troops who still live in the area. And when some of these descendants visit the exhibit, it’s very special.”

“With Valor and Honor” is open to the public Wednesdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. For more information, call 410/822-0773.

Eric Mills is the author of Chesapeake Bay in the Civil War